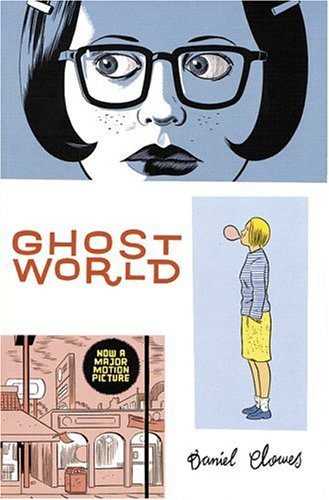

"Ghost World" is one of the few graphic novels where I enjoyed the movie more than the novel. Well, I suppose more accurately, I "enjoyed" the movie more than the graphic novel, but it is the graphic novel that does the best job of revealing a more honest depiction of that awful time between adolescence and adulthood. "Ghost World", the graphic novel, also did what all good texts should do (I believe), it laid me out on the metaphorical couch and made me come to terms with some of my own experiences as an adolescent.

David Clowes is considered to be a pioneer when it comes to the depiction of adolescence in the medium of comics, especially the gloomy, depressing, and dark type of adolescence (is there any other kind?). In fact, this text doesn't really give the reader a happy, redemptive moment. The majority of the narrative and drawings reveal these ugly (literally and metaphorically) characters and incredible awkward situations. And if the characters, situations, or narrative doesn't get you then the aquamarine, musty tint of all the panels will. Clowes claims that he used the tint to evoke the color of artificial light of something akin to a flickering television, which is appropriate to the overall theme of the graphic novel (which we will get to), but I think it also gives it this sickly, annoying, and almost aged/decaying feel to whole work.

In a nutshell, "Ghost World" follows longtime friends Enid and Rebecca as they face the uncertain future of life after high school and the fast approaching end of adolescence. Enid is constantly changing her appearance, is loud, and generally gives off the vibe that she is constantly searching for attention. Rebecca, while the quieter of the two, is no less annoying in her inability to show much in the way of emotion, constant blase attitude, and follower like role. Ostensibly, Rebecca and Enid are constantly bitching, making fun of, and just being annoying teenagers. But after reading the text it becomes clear that Clowes is being brutally honest about the moment we all realize we can't be kids any more but we don't know what we are suppose to be or do. We are content to just sit in front of the television and "not do" or "not think about" anything for a while longer.You so badly want everything to turn around for Rebecca and, especially, for Enid. You want them to get into a good college, get out of town, grow in some overly ambitious, positive way. You desire the fairy tale ending for both, for them to be redeemed in your eyes.

Dear readers, it never happens.

And perhaps that is why "Ghost World" is terribly tragic and terribly honest.

I mean, is there a redeemable aspect of adolescence. Sure, we can all make up a bullshit answer that it is a time of GROWTH! EDUCATION! EXPRESSION! But let's be honest, we are all lost in some small (or large) way in our own awkwardness and inability to come to terms with the very high, adult expectations giving to us. The way in which Enid and Rebecca bitch and make fun of people reminded me, shamefully, of something my friends and I did almost on a weekly basis. It was ritual, as it seems to be in most small towns with nothing to do, to go to the 24 hour diner and drink coffee, smoke clove cigarettes, and be incredibly loud and obnoxious. At our particular location, every night an old man would come in around midnight or so. He was missing most of his lower jaw, his face horribly disformed probably from some sort of cancer. We would make endless fun of this poor old man, never to his face but all the same we all knew how mean and awful it was. And yet we did it. I look back, still filled with so much shame and try to ration why we did what we did. I think some of it was out of pure meanness, but I think a lot of it also came from fear, and our own insecurities.

The character of Enid is vital to my understanding of both my own moment of shame and, more generally the novel and perhaps adolescence itself. (*Disclaimer* if you haven't read the novel skip this paragraph) In the end Enid doesn't get into the school she wants to and Rebecca and her have grown apart for a number of reasons (boys among them). Yet, the novel ends with Enid going to a bus stop (that apparently has been defunct for a number of years) and being picked up by the bus and traveling away from her small town. In Enid, the reader understands that one doesn't merely grow out of adolescence, one has to (sometimes painfully) shed the protective comfortable skin of childhood and teenage years and jump blindly into the unknown of adulthood. In Enid we see the adolescent longing for authenticity, for an adult world. When it becomes apparent how fake the adult world is and how futile holding out for some form of authentic, honest adult life is, Enid has to take a plunge she may not be ready or really willing to take. That's where the novel ends, we will never know if she made sense of it all. But isn't that a truth as well?

The movie, released in 2001 and directed by Terry Zwigoff, is more of a variation on a theme than a true rendering of the graphic novel. Without going into too much detail, characters are added, a love story (of course there is a love story, it's a movie what did you expect?)that isn't in the book, and, disappointingly, Enid and Rebecca's friendship is downplayed. When Enid leaves town at the end, whether because of the changes from graphic novel to movie or something else, we are cheering her as opposed to honestly accepting her leaving as a terrifying try at leaving behind adolescence.

The movie's great on its own, but the book is more important in its ability to force a critical eye on your adolescent self.

You still with me reader? I hope so. Don't worry, happier times (fingers crossed) are ahead.

Until next time,

GN

I do tend to agree for the most part, thanks for the review!

ReplyDelete